The Decentralized Future Series: A New Age of Investing

by Alex Shelkovnikov3/13/2018

Alex Shelkovnikov is a co-founder of Semantic Ventures, a venture capital firm supporting relentless builders of the new decentralized economy. Prior to that Alex led investments at Deloitte Ventures and Deloitte’s blockchain business in the UK. He also co-founded an identity management platform Smart ID.

This is the second blog post in the Decentralized Future Series. You can check out the introductory post here.

In this post, we are going to explore the paradigm shift of investing in the context of decentralized applications. First, we will briefly explain the history of venture funding and how it evolved in the last few decades. Second, we will discuss the current situation around crowdsales and ICOs. Finally, we will glimpse into the future and look at what’s coming.

A Brief History of Venture Capital

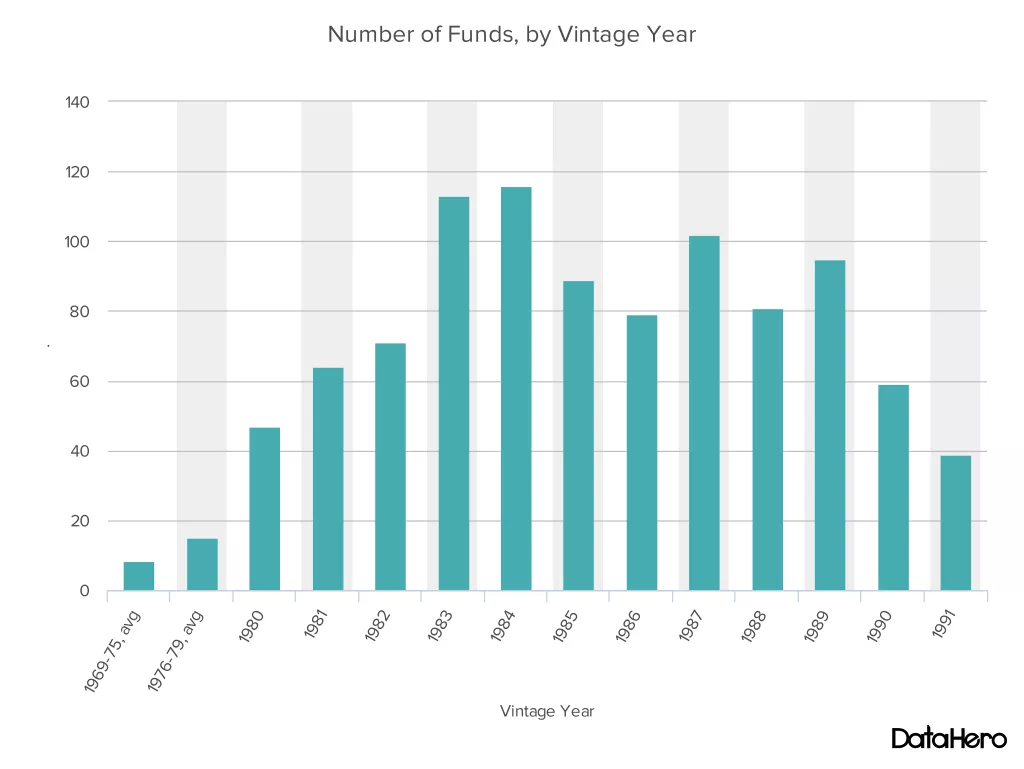

Although the first VC firms started in 19461, there were really few players and deals until the late 1960s. At that time, nobody would invest in your startup or small business if you didn’t have sufficient cash flows and revenue projections to justify it. The microcomputer industry arose in the 70s and great companies like Apple and Genentech were created. In the 1980s VC went through several ebbs and flows. During this decade, there was only one constant: Investors saw higher returns when they were optimistic enough about the future to enter ‘risky’ and disruptive markets2.

Successes like IBM contributed to and expanded this belief. Venture capital and angel investors played a pivotal role in the success of the hardware era and subsequent software age. Then, the Internet happened. Suddenly, you could start a startup with a lot less capital and compete with incumbents who had a lot more.

Then the dotcom bust happened. Surprisingly, trust in Internet ventures was regained quickly. A great small team could build a product and compete with giants like Oracle or Yahoo. Paul Graham saw this first-hand with ViaWeb and then co-founded Y Combinator on the shoulders of this premise. There was incredible growth in the 2000s and many other investment entities like micro funds, syndicates, accelerators or corporate incubators appeared. If you want to dive deeper, Andy Bromberg gave a great talk about it at YC Investor School.

The Arrow of Investing

For a long time, deal flow was restricted. You could only get access to quality deals if someone from your network connected you to the company that was raising money. More importantly, this usually meant you needed to be close to Sand Hill Road. Only a handful of people got the chance to participate in the first round of Microsoft, Oracle, or Amazon. If an average person wanted to invest in one of these companies, they usually had to wait until the company went public using an IPO process.

That being said, companies used to go public a lot earlier in their life cycle. For example, Amazon issued its initial public offering only three years after its inception.3 That led to a probably higher ROI expectation for IPO investors because there was more room to grow for these companies.

Unfortunately, the number of IPOs has been decreasing dramatically in the last decade due to a combination of high costs, bureaucracy burdens and less liquidity.45 Companies remained private longer and new investment options appeared. Public mutual funds, hedge funds, private equity buyout firms, sovereign wealth funds and family offices provided the capital required for companies to remain private.

Under these conditions, the People’s NEA (National Endowment of Arts), aka Kickstarter, was created in 2009. Crowdfunding was born. Crowdfunding gave everyone a chance to support new creative products and art. A year later, AngelList was funded to achieve the same goal with companies and democratize the investment process. However, there was still a big problem. Only accredited investors under the SEC rules could invest in securities in private offerings (for all practical purposes). Thanks in part to the Crowdfunding Exemption movement, the JOBS Act was signed in 2012. Everyone could finally participate in crowdfunding to receive stock (securities) issued by the companies. When it came into effect three years later, equity crowdfunding sites like WeFunder and Republic appeared.

If you step back, you can see a trend towards democratization. Now, there is greater access to deals that might have been entirely private before. However, the amount of companies that choose to raise through these new channels is relatively small and the public access to the best private startup deals remains restrictive. The fragmentation of the crowdfunding scene, the limitations on the amount you can raise and the bureaucracy burdens have prevented this route from becoming the path for the standard early stage startup.

Bitcoin Enters the Scene

Just before Kickstarter was created, the Bitcoin whitepaper was published. It wasn’t an investable asset at that time, let alone usable for raising funds. There were no exchanges, and you could only obtain bitcoins through mining. In 2010, the first exchange BitcoinMarket.com appeared, and only a few months later, Laszlo Hanyecz made the first real-world transaction when he bought the infamous pizzas for 10,000 BTC6.

Order books were thin, liquidity was non-existent, and volatility was high. Mt. Gox appeared in July 2010, becoming the entry point into cryptocurrencies for avid investors. Before its demise in 2014, it handled up to 70% of the total BTC volume. Mt. Gox proved the market and other exchanges like Coinbase would follow suit in 2012. The market started to mature, confidence in Bitcoin rose and liquidity increased.

In 2013, the first initial coin offering or ICO appeared. Mastercoin raised 4,700 BTC ($5 million at the time) in bitcoins in exchange for their tokens7.

The Rise of ICOs

For the first time in history, we’ve witnessed a cryptographically secure way to prove ownership of an asset available to pretty much anyone in the world. This decentralized ledger opened up an opportunity for companies to store shareholder registries on the blockchain. Initially, companies and projects like Mastercoin were performing crowdsales and storing information about contributions and ownership on the Bitcoin blockchain. Then came Ethereum which further expanded capabilities by enabling token issuance and allowing you to collect funds via a smart contract.

Ethereum has opened up the floodgates and popularised this new fundraising mechanism, the initial coin offering (ICO). Ethereum itself ran a successful fundraise in July 2014 through an ICO and obtained 31,591 BTC which at the time was worth $18.4m. Since then, over the past four years, we’ve seen incredible growth in the total amount of money raised by projects (decentralised and not really decentralised) via an ICO8.

Furthermore, it enabled projects to raise a small amount of money from a big number of highly engaged individuals. Individuals with ‘skin in the game’ that would help kickstart and evangelize the project. Unlike traditional investment opportunities available to retail investors, here you could invest in a project at the initial stage. You didn’t need to know the founders, or angels or have any particular connection to invest in it. Investments were democratized. However, there was a tradeoff. Everyone could invest in high return investments early in the project. On the other hand, shady projects could take advantage of and scam unwary believers.

A Game of Regulations

There has been a lot of uncertainty about legislation around ICOs since the beginning. Mastercoin’s board stated at the time of the ICO: “There’s no promise of dividend or equity. You’re just buying a password to access this software, and you should do that if you think that software is valuable”9. Mastercoin was claiming that their tokens were not securities. This point is critical because if you are selling a security to US investors, or if you are a US-based organization or person selling a security to even non-US investors, you need to comply with SEC requirements and regulations.

Mastercoin was careful with the language, and they may have had a point about not being a security. Many other projects have raised funds through ICO by selling what they claim to be a utility token. However, not all of them are.

ICOs raised $6.5 billion last year. This gold rush has attracted many dubious projects. Bitconnect being the most infamous example. It’s good that the SEC is trying to protect retail investors from scams and Ponzi schemes. They’ve issued subpoenas and challenged the utility status (non-security) of several token sales. Exuberance swung the pendulum way too far in one direction.

Navigating the US law in this context has been difficult. Last fall a Simple Agreement for Future Tokens was released. This SAFT, developed by Coinlist, AngelList, Protocol Labs and Cooley, was an extensive effort to formalize a framework for compliant token sales in the US. This initial SAFT even went against the open ethos of cryptocurrencies and limited the sale to accredited investors only. Some examples of crowd sales performed through the SAFT are Blockstack (partially) or Filecoin. However, recently, Chairman Clayton of the SEC has raised doubts about the validity of the SAFT and claimed: “I believe every ICO I’ve seen is a security”10. One thing is certain, many of the tokens that were issued potentially fall under securities rules. The pendulum is now swinging back.

Where does that leave us? An ICO issuer could still operate under the assumption that their token is a security, and conduct a token sale under the existing framework of securities regulations. Some examples:

A. International ICO without US Investors. That would involve following Regulation S, as well as KYC requirements and making sure no US investor participates in the sale. That effectively means the token cannot be listed on any exchange for at least a year.

B. Sale to US Investors through Reg A+. Sales to non accredited investors would be permitted and up to $50M can be raised. It’s a non-trivial endeavor though, because it technically is a public offering registration process (albeit an abbreviated one). This takes at least several months and a running dialogue with the SEC for the eventual approval.

C. Sale to US Investors through Regulation D, 506(c). Only accredited investors are allowed. General solicitation is also allowed under these rules, but reasonable diligence must be done to confirm that each person who purports to be an accredited investor is actually an accredited investor. A securities filing is required but preapproval from the SEC is not. 22xfund is raising an ICO using this method.

More guidance from applicable regulators could further protect and safeguard this funding model. For example, other regulators like FinCEN have suggested that cryptocurrencies might be subject to money transmitter laws, not just securities regulations. In an ideal world, good projects would have a clear and relatively frictionless path to raising a reasonable amount of money from an open network of people that believe in the project. Albert Wenger from Union Square Ventures advocates for a Safe Harbor as a potential solution. Another interesting alternative is the use of PICO, a token sale where secondary trading is disabled via the smart contract of the R-token.

Designing / Picking a Winning Network

Regulations are just a piece of this complex puzzle. When you fundraise via crowd sale, you usually receive BTC or ETH, and you give your project-specific token in return. Investors should be able to understand what drives the price of the token now and in the long term. Due to the monetary incentives, network effects are maximized and it is likely that networks will follow a Power law, maybe even more extreme than with regular startups. Following this logic, the winner in every sector would be more valuable than all the other candidates combined. It is therefore critical for investors in this space to be able to select the most likely to triumph. Designing a winning network isn’t a trivial task. It involves optimization of a full set of critical components most of which should work well simultaneously. These components are somewhat unique to decentralised platforms and protocols and have not previously featured as core elements until now. These lay the foundation of a new discipline, crypto economics or token economics. In this section, we are going to talk about how monetary policy, token model or token distribution can greatly affect outcomes.

Due to unique properties associated with decentralised consensus platforms and applications, every project that issues a token can effectively act as an equivalent to a central bank. It means developing their own monetary policy, inflationary mechanisms, ecosystem incentivisation etc. This requires unique skills not only by the teams designing these models but also by the investors supporting these projects. The first blockchain-based network, Bitcoin, introduced its own monetary policy, with its limited supply and predictably decreasing monetary inflation (although you could argue it often acts as a negative inflationary currency due to private key loss and other circumstances). Bitcoin’s policy has been covered extensively, is well understood and is regarded, together with censorship resistance and some of the other properties, as one of the core elements that justifies growth in value of the currency and the underlying network.

Many different projects are now innovating around the monetary policy. It acts as one of the important differentiators for decentralised protocols because it modifies the economic incentives for their participants. For example, Ethereum, in contrast to Bitcoin, has no cap on the total supply of Ether in circulation. It was originally designed to promote inclusiveness of the Ethereum platform for global economic and social systems11. The rate of Ether issuance has since been an active area of debate within the Ethereum community. These decisions coupled with the difficulty adjustment act as a significant lever driving the economics of the network.

Another example of a project where monetary policy acts a significant differentiator is Basecoin. It is designed to have an unique mechanism that allows the network to algorithmically adjust the token supply in response to market changes to maintain a stable price12.

One more important component that needs to be well thought through is the token model and its derived properties. Tokens can act as a powerful incentivisation mechanism to engage community around protocol development. When designed well, they facilitate network governance (e.g. through voting based on the quantum token ownership, specific tier types of a token or various other models). They can also act as a reward mechanism for performing useful work on the network (e.g. securing the protocol) or enable game theoretical features (e.g. a mechanism for staking). They could also help us curate high quality lists (e.g. a token-curated registry) or to prove the ownership of an unique digital asset (via non-fungible tokens). Finally, when tokens are designed to replicate some or all properties and functions of money, often there are hard choices to be made between optimising for a better store of value, a medium of exchange or a unit of account, which boils down to optimising for security, monetary policy and utility.

Distribution mechanism also plays a big part in assessing the future value of a project. The usual indicators to look for are transparency, fairness of distribution as well as sufficient longer term incentives (e.g. a token option pool) for the developer community and ecosystem. As we mentioned, it also has to be compliant with the (known) legal boundaries and regulations. Distribution mechanisms could be designed to promote healthy network behaviours. For example, many projects choose to sell a portion of tokens to the public claiming they need broad user adoption. In reality, however, only a small fraction of projects actually requires it. Although it is true that distributing tokens to a broader base of contributors might be a good way to create worker incentives, the majority of tokens distributed in such a way would usually end up in the wrong hands compared to the original intent. The original objective could be better achieved, for instance, through a targeted airdrop or airdrop in return for performing specific actions (Byteball is a famous example of this).

Multi-faceted Networks

As we mentioned in our previous post, the true power and opportunity that decentralized technology has opened up started with the Nakamoto consensus. It offered a solution to reach agreement on a global distributed peer-to-peer network in a trustless environment. Multiple subsequent variants and new competing consensus mechanisms have since created a healthy competition within the space. Targeting use cases and applications where the benefits of decentralization are strong, the main objective of these new decentralized technology platforms is to design a better solution for solving the scalability trilemma optimizing for one or two of the three properties of blockchain systems: decentralization, security and scalability. When looking to invest in a decentralized consensus platform or protocol, it is essential to be able to assess the trade-offs and benefits of a suggested consensus mechanism and how well they are optimized for a set of intended applications of the platform.

Given a specific market, consensus protocols aim to reach their optimal design by reacting and adapting to their unique characteristics. Alvin E. Roth in his book “Who Gets What and Why” has masterfully described real world principles and examples of efficient market design and some of these are applicable to decentralized markets. In effective markets, the distribution of rewards is often unfair and almost always deliberate. As networks evolve they’ll have to adapt some of their key design parameters appropriately to react to the changing dynamics and landscape. In the development phase, creators will have to cater for a different set of stakeholders than in the later phases. Teams that are aware of this evolution, are able to transition their projects accordingly and lead their communities during their life.

This makes effective governance of decentralised networks crucial to the long term sustainability and success. Our belief is that governance is going to become the make it or break it factor. We are going to explore this topic further in a future post in the series.

In short, crypto economics need to make sense and be carefully crafted for every protocol/platform. It is, however, not the only thing that needs to stand out when choosing a winning network. Decentralization score, community management, developer activity and community engagement on social channels like Telegram, Reddit, or Discord are signs of a healthy and booming community.

In the end, do not forget about startup fundamentals. It is again all about the team. Pick the most effective and motivated team, because they are likely to build the strongest community of contributors and users around the project. Market is obviously another key factor that can pull a great product from the right team. Especially in an environment where many founders talk about “decentralized” or “censorship resistant” when asked about their competitive advantage. End users don’t necessarily care about those in most cases. Always ask yourself, what’s the decentralized edge? The use of decentralized technologies needs to be justified to provide a defensible advantage against incumbents. Otherwise, it is just buzzword soup to entice unwary investors.

A Quick Note on Valuations

After deciding that you believe in a cryptocurrency you still need to know how to assign a proper numerical value to it. It’s also useful to benchmark the asset against other cryptocurrencies and crypto assets (tokens). The most popular site for this, CoinMarketCap, uses total market cap as a benchmark. Onchainfx goes a step further as it accounts for the total future supply. Network Value to Transactions Ratio popularized by Nic Carter, Chris Burniske and Willy Woo is another interesting approach. You divide the network value by the number of transactions. The lower it is the cheaper the asset. These methods reflect the current price but they don’t explain the fundamental value behind these assets.

In order to make estimations about the future value of an asset, the key is to consider the velocity of money. Velocity is basically the number of times the same token changes hands in a specific timeframe. Applied to the equation of exchange where MV=PQ, one can see that the velocity of money is inversely proportional to the price of an asset. However, there is a floor as to how low this velocity can go without collapsing to zero. There seems to be a sweet spot for velocity. This is a complex topic and the current approach to use the Quantity Theory of Money may prove to be incorrect13. Many factors can affect different elements of this equation. For example, in a world of interoperable networks with low friction exchange capability, crypto assets (especially utility tokens) could be seen through the lens of working capital where one doesn’t need to store a large number of tokens to facilitate the utility function of a blockchain protocol. Therefore higher token velocity and potentially lower network value of utility protocols than currently assumed14. Governance models could also influence velocity15. This is an evolving field and new valuation approaches are appearing quickly suggesting both clarification of definitions and alternatives such as a two-asset model with endogenous velocity.161718

Winter is Coming

There has been a lot of optimism and trust in the potential of these projects in the recent years. It has offered incredible returns. Recently, we have seen how monster ICOs like Telegram are planning to raise massive amounts of money. Other projects like Status or Tezos have shown that it’s important to think through the impact on the underlying network, community as well as think through the governance models appropriately before running the public sale.19

Some projects are exploiting a system that blossomed as a solution to create innovative networks protocols that would have remained underfunded otherwise. These ICOS betray the community ethos. It is only normal that this exuberance attracted the regulatory bodies. Due to this increased scrutiny, however, seems like we may be headed to an ICO winter, at least until regulation compliant ICOs prevail.

Conclusion

There has been a lot of excitement in the last twelve months around ICOs. Token sales appeared as a promise for projects to raise a small amount of money from early contributors/developers to create innovative protocols and networks together. They democratized access to investing and let anyone participate from the early stages.

Some of the sophisticated investors have also been supporting this space for years. Mainly angel or venture capital investors either bought tokens personally or invested in blockchain startups via equity-based rounds of funding. Recently, however, we’ve seen emergence of a large number of other types of investors joining (specialised hedge funds, family offices, institutions etc.). This led to abundance of capital available to early projects and the emergence of token-based private rounds and pre-sales. These private rounds frequently led to some of these investors liquidating their positions as soon as tokens are listed (or even before) at the expense of public contributors.

A balance needs to be achieved. Too much private capital can definitely harm network growth. We believe becoming a private investor in a great decentralized project early on is going to become more and more difficult. That said, a sophisticated investor with deep crypto expertise can take the early risk and help the team solve problems around crypto economics, governance or token issuance in a way that most traditional VCs are not necessary well equipped to do. Should their contribution prove to be effective for projects within the decentralised technology space venture investors will still stay relevant and able to fund some of the best teams out there. A sophisticated investor can also help both navigate the complex regulatory situation and provide funding until the network is ready to make a public sale or any other type of token distribution.

The truly meaningful decentralized networks or protocols may need to distribute their tokens amongst their users to align the incentives of its early adopters. However, they also need to be aware of the most effective and safe ways to do it. Regulation exists to protect retail investors and consumers from unfair practices, misleading and fraudulent activity. We hope regulatory bodies provide clear guidelines to these projects and apply a sensible approach to safeguard innovation. Once clear regulations are in place, trust in the future of this disruptive space will increase, attracting bigger players into the market that will, in time, bring more capital to new ventures.

Note: this post is for informational purposes only and not for the purposes of providing legal, investment or any other form of advice. You should contact your own advisors (legal, investment or otherwise) with respect to any particular issue or problem.

Thanks to Craig Cannon, Yannick Roux, Stefano Bernardi, Andy Bromberg, Raúl San Narciso, Jason Kwon and Jared Friedman for reading drafts of this post.

Notes

1. J.H. Whitney – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J.H.Whitney%26_Company and American Research and Development Corporation. (ARDC).↩

2. VC in the 80s – http://reactionwheel.net/2015/01/80s-vc.html.↩

3. Amazon – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amazon_(company).↩

4. Where have all the IPOs gone – a16z: https://a16z.com/2017/06/19/ipos/.↩

5. IPOs by year – Statista: https://www.statista.com/statistics/270290/number-of-ipos-in-the-us-since-1999/.↩

6. This Pizza cost $750,000 – Vice: https://motherboard.vice.com/blog/this-pizza-is-worth-750000.↩

7. Backed by $5 Million in Funding (4,700 BTC) – MarketWired: http://www.marketwired.com/press-release/backed-5-million-funding-4700-btc-mastercoin-is-building-flexible-new-layer-money-on-1859067.htm.↩

8. ICOs in 2017 – BusinessInsider: http://www.businessinsider.com/how-much-raised-icos-2017-tokendata-2017-2018-1.↩

9. The First ‘Bitcoin 2.0’ Crowd Sale – Forbes: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kashmirhill/2014/06/03/mastercoin-maidsafe-crowdsale/#6b5a08c7207d.↩

10. SEC subpoenas and SAFT – Venture Beat: https://venturebeat.com/2018/03/03/sec-subpoenas-show-the-saft-approach-to-token-sales-is-a-bad-idea/.↩

11. The issuance model in Ethereum – https://blog.ethereum.org/2014/04/10/the-issuance-model-in-ethereum/.↩

12. Basecoin Whitepaper – http://www.getbasecoin.com/basecoin_whitepaper_0_99.pdf.↩

13. The Quantity Theory of Money for Tokens – https://blog.coinfund.io/the-quantity-theory-of-money-for-tokens-dbfbc5472423.↩

14. An (Institutional) Investor’s Take on Cryptoassets – https://medium.com/john-pfeffer/an-institutional-investors-take-on-cryptoassets-690421158904.↩

15. Governance and Velocity – https://twitter.com/L1AD/status/968833504812371968.↩

16. On medium of exchange valuations – https://vitalik.ca/general/2017/10/17/moe.html.↩

17. How to Value a Crypto-Asset — A Model – https://medium.com/@wintonARK/how-to-value-a-crypto-asset-a-model-e0548e9b6e4e.↩

18. A new approach to cryptoasset valuations – https://medium.com/blockchannel/on-value-velocity-and-monetary-theory-a-new-approach-to-cryptoasset-valuations-32c9b22e3b6f.↩

19. Tezos ICO Debacle – https://cointelegraph.com/news/what-lessons-can-be-learnt-from-tezos-ico-debacle.↩

Categories

Other Posts

Author

Alex Shelkovnikov

Alex is a co-founder of Semantic Ventures, a venture capital firm supporting relentless builders of the new decentralized economy. Prior to that Alex led investments at Deloitte Ventures and Deloitte