FDA: Orientation for Early Stage Startups

by Reshma Khilnani, Jared Seehafer3/2/2021

One of the most common topics YC Bio founders ask us about is the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the broader regulatory environment. Obviously, with a topic this broad, there’s no way to give a single or simple answer; one could write a whole book on the subject (and many have). But as a starting point, we wanted to touch on some of the most important concepts bio founders should think about. We’ve distilled them down to their essence, and we hope this article will point you in the right direction as you move forward with your startup.

In the interest of brevity, we’re limiting this conversation strictly to the FDA, and leaving out its international counterparts, such as the EU’s EMA or China’s NMPA. That’s because although the general principles we cover here are similar from country to country, the particulars vary greatly depending on the country in question.

The FDA is the federal regulatory body in the United States that oversees the development of medical products (e.g. drugs, biologics, diagnostics, medical devices), food products, tobacco and cosmetics. All companies making these products and wishing to sell them in the United States, regardless of where they are physically located, will need to comply with FDA regulations.

Here in the United States, a primary function of the FDA is regulating companies’ claims about their products. For example, if you claim your drug treats diabetes, or your lab test diagnoses diabetes, the agency expects you to present data irrefutably demonstrating those claims. And it requires that you satisfy their regulatory approvals process before you market your product in the US. It’s illegal to say your product diagnoses or treats a disease without a green light from the FDA, and it has the authority to demand a recall or even to physically seize the entire supply of your product if it determines your product poses a meaningful public health risk.

Functionally, the FDA’s oversight can be grouped into two broad categories, each of which we’ll dive into below:

- Granting marketing approvals to products

- Ensuring ongoing regulatory compliance of the companies making them

Approvals

Developing and bringing a product to market will, with the exception of a limited class of products1, require explicit FDA marketing approval.

There are, broadly speaking, three types of interactions that you may have with the FDA as you bring your product to market:

- Pre-submissions. Here, you preview your intentions for the FDA, after which they give you feedback on your progress and approach.

- Clinical trial authorizations. With this step, you request permission to test your new (or in FDA’s parlance, “investigational”) product in people prior to explicit approval.

- Marketing approval submission. Your official request for regulatory approval to market your product.

Pre-Submissions

A pre-submission (or PreSub) is exactly what it sounds like: an interaction with the FDA before you file your official marketing approval submission. There are two important reasons to do this: (a) to get permission to conduct clinical trials or, (b) to get approval to market your product. PreSubs are optional, but companies often choose to do them during the early stages of product development because they want a sense of what kind of clinical evidence the FDA will require before granting its approval.PreSubs can also be valuable during product verification when companies are giving the FDA a preview of their submission seeking permission to conduct clinical trials (more on that in a moment).

The kinds of companies most likely to pursue PreSubs are startups and companies developing a product that’s novel in technological approach or indications for use. For startups, a PreSub provides an opportunity to build a relationship with the FDA prior to the formal marketing approval process, as well as to make sure you’re on the right track. For established companies, sharing the product with the FDA and getting its feedback on your approach and plans for demonstrating product performance, safety, and efficacy can go a long way to reducing your product’s exposure to regulatory risk.

While the PreSub process is non-binding, you don’t want to waste the FDA’s time–and sour your relationship with it off the bat–by sending the agency a blank sheet of paper and/or asking too many open-ended questions. Successful PreSubs usually give the FDA a broad range of information it can use to evaluate the product’s design, intended use, and testing to date. It will also ask specific questions that are likely to elicit actionable responses. It’s unreasonable to expect the FDA to try to design your product for you, so a common practice is to propose answers to the questions and ask “does the agency agree?”

Fortunately, the FDA provides helpful and easy-to-parse PreSub Guidance documents that are worth reading.

Clinical Trial Authorizations

While some products (particularly certain medical devices) require only preclinical testing to obtain regulatory approval, most require clinical trials calling for explicit authorization from the FDA. In effect, you’re seeking permission to investigate a novel product.

If you’re making a new drug or biologic, you’ll go through the Investigational New Drug (IND) process. An IND application seeks permission for you and your clinical investigators to proceed with the trial. Getting approval for an IND application requires that you do sufficient preclinical testing to demonstrate that it can be safely used in humans. This type of testing typically involves some amount of animal testing, and you must provide data on how you’ll manufacture or produce the drug. In addition, the FDA demands your plan for testing the product’s safety and efficacy in humans throughout the three Phases of therapeutic clinical trials2.

If you’re making a new medical device or diagnostic, you’ll go through the Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) process. This lets you conduct a clinical study to collect safety and effectiveness data for your medical device. As with an IND, you’ll need to demonstrate sufficient preclinical testing to justify patient safety, and what you hope to learn from the trial and your device manufacturing plans.

Whether you’re pursuing an IND or an IDE, you’ll have to fully explain what you want to study, who your investigators are, how safe the product is, what type of patient consent you’re requesting, and what institutional review board (IRB) has reviewed and cleared your studies.

Marketing Approval

After you’ve run all your preclinical and clinical studies and collected all the data, your next step is packaging the relevant data and seeking the FDA’s marketing approval for your product so you can commercialize it. There are numerous types of marketing approvals but all share some common requirements that must be met: thoroughly describing the product’s design, how you’ll manufacture it, its intended use and indications for use, how you foresee it changing the clinical landscape, how you’ve tested it, how the marketing approval pathway you’ve chosen is appropriate, and how the product is safe and effective3 for intended use.

There are many different types of marketing approval submissions. Which you choose depends on the type of product you’re developing and how novel it is. We describe the major ones here:

Therapeutic Submissions

There are three major types of therapeutic submissions to the FDA: New Drug Application (NDA), Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), and Biologics License Applications (BLA). Generally, traditional small-molecule therapeutics call for the NDA or ANDA while the BLA is for biologic products, which encompass large-molecule therapeutics, tissues, gene therapies, and the like.

The NDA is the most well-established category of therapeutic submissions; the majority of well-known pharmaceuticals have gone through it. And within the NDA itself, there are two categories of submissions. The first is the 505(b)(1), which companies use when seeking approval for a new drug whose active ingredients have not been previously approved. This requires extensive research and substantial resources. The second is the 505(b)(2), which companies utilize when the active ingredients of their new drug are similar to those in an existing approved drug. An example is if an existing drug that’s been approved to be sold as a tablet is being altered to be sold in liquid form. The difference in process between 505(b)(1) and 505(b)(2) is large and choosing the appropriate one is a big strategic decision for any therapeutic company.

The ANDA is reserved for the approval of generic drugs with no novel active ingredients. New generics must show “bioequivalence” to an existing product on the market.

The BLA covers a large number of therapies including blood products, vaccines, tissues, and more. Companies producing biologics should take the safety and efficacy of their product seriously, but the FDA also focuses acutely on the manufacturing process. Many biologics come from donors, and ensuring the donor process is safe is vital to securing this type of approval.

Medical Device and Diagnostic Submissions

The range of products that are classified as medical devices is huge. The term is basically a catch-all for anything used in the practice of medicine that’s not a drug or biologic. This can include stents and oxygen masks, diagnostic tests like a hemoglobin A1c test, or software like radiology viewers. Clearances for diagnostic devices can sometimes be simpler and faster than for therapeutics.

The FDA filters a medical device into one of three classifications based on its risk: Class 1, 2 or 3. Understanding a product’s risk and product code is key in developing medical devices, as they impact the level of evidence needed for approval. Product code examples include “LCP” for Assay, Glycosated Hemoglobin or “LLZ” for Image Processing Radiological System.

It’s worth noting that some medical devices are so low-risk that they require no explicit approval at all. In those cases, the FDA only conducts oversight after the fact via its regulatory compliance processes (see the “Compliance” section below). A tongue depressor is a good example, as are FSH tests.

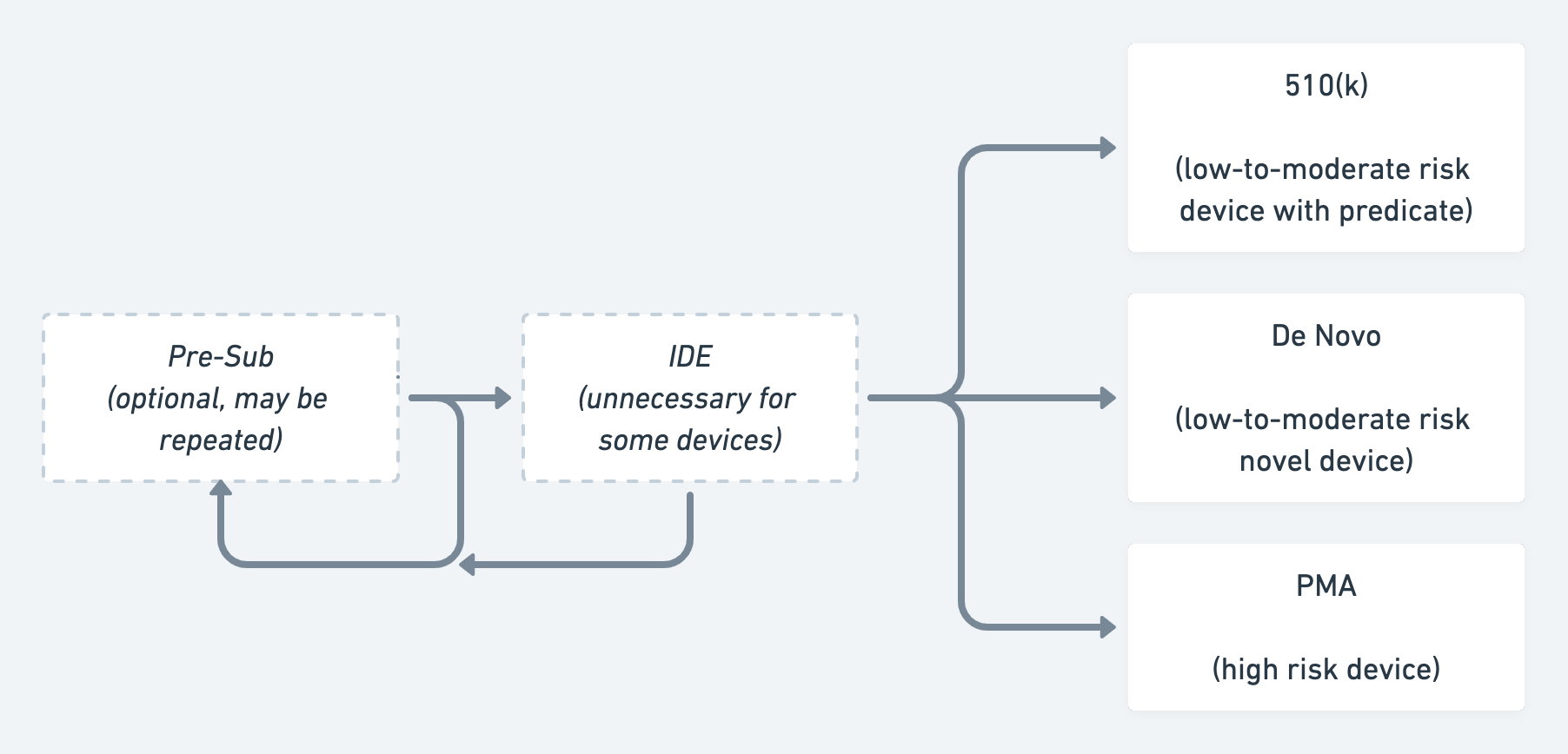

Companies whose medical devices do require approval must choose one of three types of submissions 510(k), De Novo, or Premarket Approval (PMA).

The 510(k) is the most common and streamlined diagnostic/device submission, yet can be one of the most difficult to understand conceptually. That’s because a 510(k) requires not only proving that a product works and is safe and effective for its intended use, but that it is also substantially equivalent to an existing product on the market, which the FDA calls a predicate. In a sense, seeking a 510(k) is a bit like a mapping exercise in that you must demonstrate how your product is comparable to its predicate4.

510(k) clearances vary widely in how easy they are to obtain, and how much evidence is required to obtain them5. This variance has led the academy and the media to attack the 510(k) process. As such, the FDA has proposed an alternative that requires explicit evaluation of each new product on its merits rather than the substantial equivalence paradigm. But because implementing this change requires Congressional approval, the 510(k) will be with us for a while.

While 510(k)s are the most streamlined medical device submission, PMAs are the most complicated because they’re required for any Class III product and are generally intended for medical devices supporting or sustaining human life, or which can cause grave injury. These devices often require an approved IDE and several clinical animal and human studies before approval. Although PMAs are the most difficult medical device submission to achieve, that difficulty comes with some unique benefits. For example, a product that goes through PMA cannot be used as a predicate for a competitor’s 510(k), unlike products that go through a 510(k) or De Novo.6

A De Novo submission falls between a 510(k) and a PMA. It is meant to solve a problem with the existing regulatory paradigm, which is that any unclassified product is automatically designatedClass III, even if it isn’t objectively very high risk. For instance, without the De Novo process, the ECG functionality on the Apple Watch would have been classified as having the same risk level as a pacemaker. Thus, this process allows companies to de novo classify their products as lower risk, and therefore not calling for the level of evidence needed to support a PMA. Products suited for a De Novo can include novel medical devices that are low-to-moderate risk and do not have an existing product code or classification. New digital products commonly utilize the De Novo pathway, as products of their type haven’t existed before. Diagnostic tests for emergent diseases like Ebola often follow the De Novo pathway. (However, due to the urgent need during the current pandemic, COVID-19 testing has largely gone through the FDA’s Emergency Use Authorization process).

A simplified flowchart illustrating the FDA approval process for therapeutics.

A simplified flowchart illustrating the FDA approval process for therapeutics.

A simplified flowchart illustrating the FDA approval process for devices & diagnostics.

A simplified flowchart illustrating the FDA approval process for devices & diagnostics.

Food Product Regulatory Pathways

The FDA also regulates production of food products, and offers two relevant frameworks: Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) and Food Additive Petition/Color Additive Petition (FAP/CAP).

GRAS covers products that can be safely used in food and calls for documenting how they’re manufactured, their potential to be allergenic, and their breakdown of fats, carbohydrates, protein, and nutrients.

Companies seeking a FAP/CAP clearance usually have novel food products like the soy leghemoglobin that Impossible Foods uses in its Impossible Burgers.

Emerging Therapeutic Areas

There are three types of rapidly evolving, emerging FDA-regulated fields, and founders in these fields should pay special attention to the fluid regulatory trends. Generally, these areas don’t fall neatly into the existing categories, which is why the FDA is working on new oversight methods.

Further, because products may be subject to Breakthrough Designation or The Orphan Drug Act, startups should investigate whether these programs apply to them, and if so, if they offer meaningful benefits.

Precision Medicine

Precision Medicine is an emerging medical model that proposes customized medical decisions, treatments, practices, and products tailored for specific patient sub-groups. Diagnostic testing can guide the treatment, with the tests acting as a means for subdividing patients into groups that each receive different treatments. One challenge for precision medicine product developers is that the FDA historically approves the same product configuration for use across a broad patient population, rather than for therapies targeted toward a particular patient. The FDA is initially evolving its approach in this area with Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) tests. You can find more information on this at fda.gov.

Digital Health

Historically, most companies developing “digital health” products took great pains to steer clear of product functionality that necessitated FDA oversight. In recent years, however, some new classes of products have been a priori FDA regulated, such as digital therapeutics (e.g. Pear Therapeutics’ reSET or Akili’s InteractiveRX), or AI-powered diagnostic or treatment aids (e.g. Caption Health’s Caption AI or Subtle Medical’s SubtleMR). These types of products are often very attractive and exciting because they promise software-style development timelines for a medical product. But the challenge for the developer is that FDA regulations governing software assume it’s used inside capital equipment and is neither changed frequently or tied to a hardware timeline. FDA regulations are rarely optimized for an agile, iterative style of development because they require marketing approvals for major product changes. They’re also poorly optimized for products utilizing machine learning, since the agency’s expectation is that the software is “fixed” after it grants approval.

The FDA recently created a dedicated Center for Digital Health to drive changes in regulating standalone software. Several proposals, which require Congressional approval, have been made, but as of yet nothing has been enacted. The bottom line for startups is to watch this space, especially this year.

Laboratory Developed Tests

Laboratory Developed Tests (LDTs) are those developed by a clinical laboratory and used only within that laboratory. They have historically existed in a gray area, because clinical laboratories are regulated not by the FDA but by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) under what are known as Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). Labs have historically asserted that the FDA has no jurisdiction since they’re neither marketing nor selling a test. But the agency has historically disagreed, arguing that these tests are considered In Vitro Diagnostics (IVD) and therefore subject to oversight. In certain cases where the FDA has a higher than average concern about an LDT’s impact to public health–such as recently, with COVID-19 tests–the agency has asserted its right to regulate them.

The bottom line is that the current situation is untenable, and the highly-publicized delay in getting COVID-19 tests released last spring brought more attention to this issue. Congress is considering several proposals that would effectively remove the regulatory gray area around LDTs and create a new specific regulatory pathway for this category of product. The takeaway for startups is to expect additional oversight beyond that in CLIA for these tests. When exactly that will happen is hard to say, but it could be during the Biden administration.

Compliance

Granting approval for clinical trials and product marketing is just a fraction of what the FDA does. All companies developing drug or food products, regardless of their product release schedule, are subject to compliance obligations imposed by the agency. There are three pillars of compliance to think about:

- Quality Management System / GxP: Optimizing product development and manufacturing for product quality.

- Labeling: Ensuring marketing activity is consistent with the terms of your regulatory approvals.

- Post Market Surveillance: Monitoring the safety of your product after commercial release and taking corrective action if necessary.

Quality Management System (QMS) / GxP

For most early stage companies that haven’t yet commercially released their first product, the most important thing to consider is a quality management system (QMS). Broadly speaking, this is a series of processes and procedures governing how a company ensures product quality. Specifically, a QMS aims to ensure products consistently meet customer, business, and regulatory requirements. This entails not only staying abreast of what those are, but meeting them, correcting errors to the extent possible before the product is released, and continuous improvement following release.

You may hear of terms that fit the pattern of GxP, such as Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), Good Documentation Practices (GDP), Good Clinical Practices (GCP) and Good Laboratory Practices (GLP). These GxP are best practices for ensuring product quality and fall under the same general principle of a QMS. You can think of your QMS as instantiating these GxP within the specific context of your particular company.

A QMS should be pervasive and touch on every aspect of your company. Startups often mistakenly think that they can postpone initiating a QMS until their product is on the market. But doing this likely means lying to the FDA and, at best, will incur a significant penalty. At worst, not implementing a functional QMS prior to commercialization can result in significant delays in regulatory review and/or a disastrous first audit. This will cost the company far more to resolve than what it would have spent setting up the QMS properly in the first place.

One key component of every QMS is documenting the procedures your company follows, as well as the records your company generates about product development, manufacturing, suppliers, and defects. Consequently, maintaining a QMS quickly becomes an exercise in data management and organization. Thankfully, several companies make software solutions that assist with this task. Enzyme (YC S17) is one such company. It can also assist with setting up your QMS, and can act as your regulatory consultant. We’ll discuss that in a subsequent post.

Labeling

Once the FDA has approved your product, you’ll likely want to announce it to the world in every way possible. FDA-regulated companies face a challenge in marketing communications because their products’ labeling must be consistent with the claims approved by FDA during the marketing approval. Further, the FDA considers every communication you make about your product to be labeling. One common mistake startups make is including or linking to material that discusses the product in an off-label context, i.e. for uses not specifically covered in the marketing approval. Medical professionals are free to use these products off-label as they see fit, but the companies making them cannot encourage or otherwise promote those uses.

Post Market Surveillance

Prior to approval, you put your product through testing with a small, but statistically significant sample of your projected patient population. After launch, every company making medical products must monitor their product’s performance and record all customer complaints, and report adverse events to the FDA. Depending on your product, the agency may require a more detailed post-market surveillance program, such as a post-approval study. If a discovered defect or deficiency in your product threatens patient safety, you may opt to (or be required to) provide a safety alert to your customers and/or initiate a product recall.

Conclusion

We realize this was a long post, full of technical concepts and jargon. We hope that startup founders or future founders who want to build a product that will need to be cleared by the FDA will come away with a sense of:

- What clearance types might be appropriate for your product

- What steps, at a high level, you will need to go through to get that clearance

We welcome your input and feedback. Reach out to us on Twitter at @reshmakhilnani and @seehafer.

Thank you to Uri Lopatin, Surbhi Sarna, Jared Friedman, Beth Kolko, Geoffrey Lucks, Lindsay Amos for reviewing this essay.

Related Reading:

Part 2: The Pre-Product Startup and the FDA

Notes

1. Unfortunately, with FDA, there are usually exceptions to every rule. ↩

2. We highly recommend that startups developing their first product pursue a Pre-IND or Pre-IDE. ↩

3. You’ll see “safe and effective” all over FDA’s website and guidance. This two-pronged standard is derived from the agency’s enabling legislation. ↩

4. Shift Labs (YC W15) graciously open-sourced one of their 510(k)s for the benefit of others interested to know what a finished submission actually looks like. ↩

5. As an example, YC company MedXT (YC W13) got their 510(k) relatively in the first year of the company’s life. ↩

6. As an example, YC company VenoStent (YC S20) will pursue a PMA. ↩

Categories

Other Posts

Authors

Reshma Khilnani

Reshma Khilnani is a Visiting Group Partner at Y Combinator. She was co-founder and CTO of MedXT, a medical image management software company funded by Y Combinator in 2013, acquired by Box. She has

Jared Seehafer